by Douglas S. Massey, Len Albright, Rebecca Casciano, Elizabeth Derickson, and David N. Kinsey. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013. 288pp. Hardback. $35.00. ISBN: 978-0-691-15729-0.

by Douglas S. Massey, Len Albright, Rebecca Casciano, Elizabeth Derickson, and David N. Kinsey. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013. 288pp. Hardback. $35.00. ISBN: 978-0-691-15729-0.Reviewed by Samuel B. Hoff, Department of History, Political Science, and Philosophy, Delaware State University. Email: shoff [at] desu.edu.

pp.145-148

Four recent books (all published in 2013) address different dimensions of the juxtaposition of race, poverty, and residential life. Perhaps surprisingly, only one of these addresses the urban core: Patrick Sharkey investigates the multigenerational nature of urban neighborhoods and its negative consequences for African Americans. He contends that changes must address this phenomenon and offers several suggestions to do so. The other books focus more on the suburbs. Elizabeth Kneebone and Alan Berube focus on suburban poverty, which they assert to be increasing due to a struggling economy, immigration, population dynamics, and shifts in affordable housing and jobs. In order to reverse that trend, they propose modernizing services and improving resources. Leigh Gallagher traces the flight from suburbs caused by decline of the nuclear family, the appeal of cities, and the means to travel there. She provides evidence that population growth has occurred in certain suburbs which have adopted environmentally-conscious policies and which have walkways for residents. The book under review asks, Can a housing development for select low-and-moderate-income minority residents be successful in an upscale suburban setting?

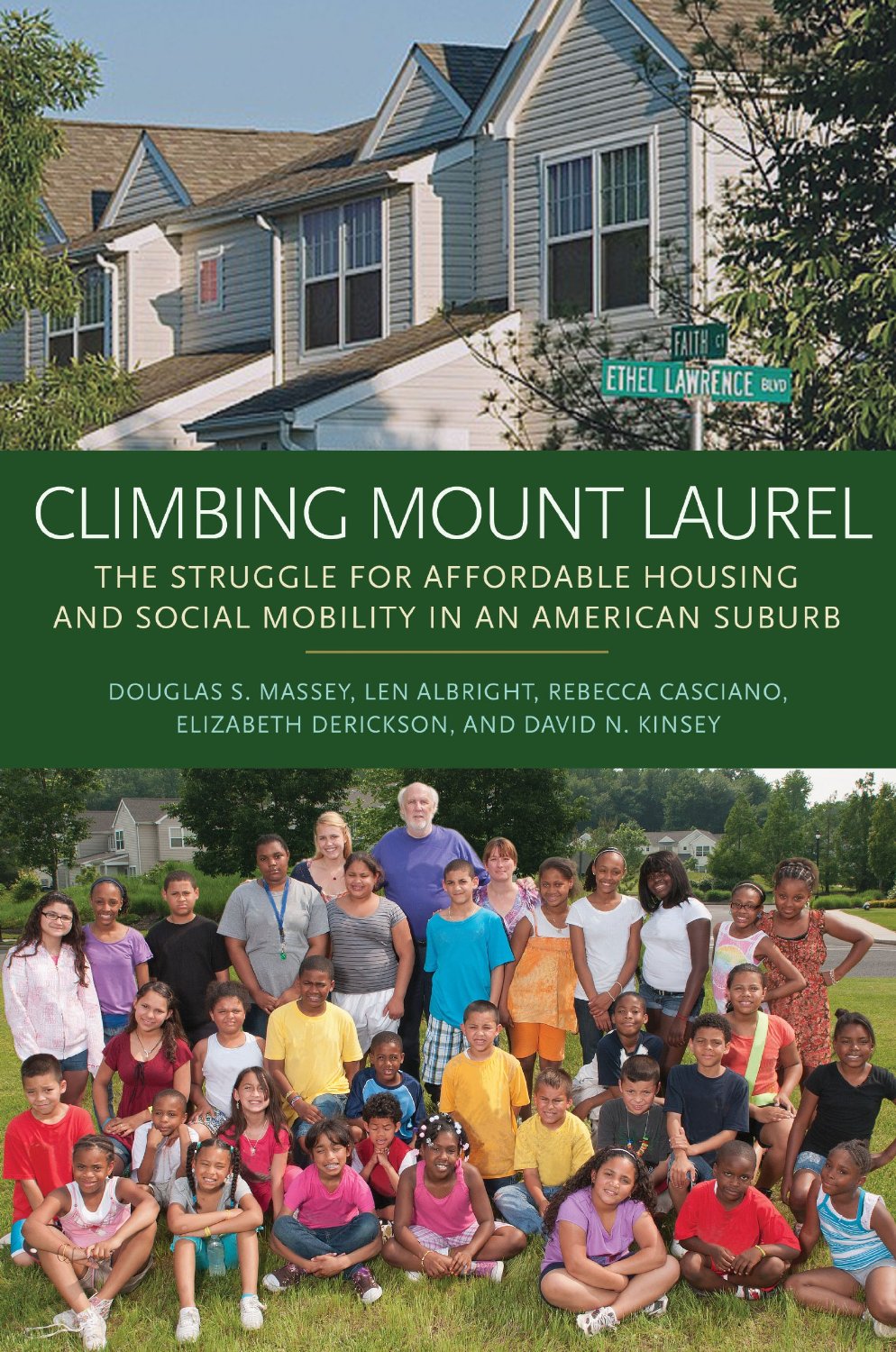

That question is answered emphatically in the affirmative in this monitoring report based on a long-term study of the Ethel Lawrence Homes (ELH) project in Mount Laurel, New Jersey. Princeton University sociology professor Douglas Massey and Princeton public and international affairs lecturer David Kinsey, together with Princeton sociology Ph.D. candidate Elizabeth Derickson, are joined by Northeastern University sociology professor Len Albright and CEO Rebecca Casciano as participants in research that began in 2009. The team probes the ELH’s history and assesses its impact by employing legal analysis, social science techniques, and policy advocacy. The study is funded by public (Department of Housing and Urban Development) and private source (MacArthur Foundation) grants. The success required sustained effort by activist groups, two state Supreme Court victories, and subsequent legislation.

Chapter 1 begins by offering a remedial course on real estate and the importance of its location within a community. The authors assert that because the most important barriers to residential mobility in the United States have been racial in nature, the “end result was a universally [*146] high degree of urban racial segregation in mid-twentieth century America that only began to abate in the wake of landmark civil rights legislation passed in the 1960s and 1970s” (p.2). It was in that kind of political and cultural environment that Ethel Lawrence – an African American resident of Mount Laurel – and her colleagues formed the Springville Community Action Committee (SCAC) of South Jersey in 1967 in order to bring affordable housing to the Mount Laurel area. Launched in 1969, the SCAC housing project ran into immediate opposition from local government and residents. Following an NAACP-led lawsuit in 1971, the New Jersey Supreme Court issued landmark rulings in 1975 and 1983, referred to as MOUNT LAUREL I and II, – which created and expanded the Mount Laurel Doctrine, an obligation of local communities to eliminate exclusionary zoning practices and provide their fair share of affordable housing resources. Still, it took another fourteen years for the Mount Laurel Planning Board to approve the SCAC housing project, renamed after Ethel Lawrence following her death in 1994. The Ethel Lawrence Homes project completed its first stage of construction in 2000 and a second phase in 2004. For Law and Politics Book Review readers, then, most of the book is concerned with policy implementation and evaluation, after the legal victory has been secured.

Chapter 2 covers the aftermath of the New Jersey Supreme Court’s MOUNT LAUREL decisions. After the 1983 ruling, the New Jersey legislature passed the Fair Housing Act in 1985. That law withstood several challenges over its constitutionality. The Mount Laurel Doctrine has been a political football in New Jersey since its establishment. For instance, present governor Chris Christie unsuccessfully sought to eliminate the New Jersey Council on Affordable Housing, a state agency created concurrent with the 1985 law.

In Chapter 3, Massey et al. explain the features of the plan for Ethel Lawrence Homes which played a large part in the success of the project. First, although the density zoning for the ELH project was set at 10 units per acre under a 1985 settlement, the final layout contained just 2.25 units per acre. Second, the ELH project developer was also its manager, Fair Share Housing Development (FSHD), which was founded by one of the attorneys representing the project in the courts. Third, the ELH project took into consideration the immediate surroundings so as to emphasize compatible and appealing buildings and landscape architecture. Fourth, social factors played a role as far as selection of residents and placement of resources. Fifth, the FSHD organized a Neighborhood Watch organization within ELH whose monthly meetings permitted residents to discuss security and other issues freely. Finally, ELH benefited from public and private financing.

In Chapters 4 and 5, the authors evaluate how ELH’s first decade affected local crime rates, property values, and taxes, the common reasons neighborhoods object to accommodating low income housing. Chapter 4 reports the results of a multiple control-group time series design using demographic data from census records, public property records, postal route addresses, and surveys of residents. Chapter 5 compares crime rates at ELH to three similar [*147] communities outside Mount Laurel from 1990 to 2009, plots home price trends in and out of Mount Laurel from 1994 to 2010, and illustrates property tax rates in Mount Laurel and similar communities from 1997 to 2010. The authors find that crime fell before and after completion of ELH everywhere in the study; that there was no significant differences in the rate of home-price increase between Mount Laurel and other comparable townships; and although variable, property taxes are still at a lower rate presently than when ELH opened in 2000.

In Chapters 6 through 8, the researchers furnish findings based on interviews with ELH residents and nonresidents in 1999 and 2009 to show the benefits of the project. Despite being younger, single, and more racially diverse than other communities, ELH residents were not seen as responsible for crime or other ills affecting Mount Laurel. In examining a series of quality-of-life concerns, the authors determine that ELH residents suffered less exposure to violence, social disorder, and negative life experiences and a higher level of mental health than nonresidents. These advantages were discovered to carry over to education of children and views of parents toward education. Together, the aforementioned traits improved the economic independence of ELH residents.

In Chapter 9, the authors synthesize findings of the study. In addition to those features identified in Chapter 3, they add another which perpetuated the success of the ELH project: the range of affordability built into the homes, ranging from a cost equivalent to 10 percent of the local county’s median income for one person to 80 percent of the area’s median income for a five-person family. Massey et al. conclude that their study of the ELH project demonstrates that “an affordable housing project for low-and-moderate-income minority residents can indeed be developed in an affluent white suburb without imposing significant costs on the surrounding community or its residents” (p.186). On a larger level, they argue that projects like ELH constitute “an efficacious means to lower levels of racial and class segregation while increasing social mobility for disadvantaged inner-city residents” (p.193).

On the positive side, Massey and his colleagues garnered the 2013 Paul Davidoff Award from the Association of Collegiate Schools of Planning for their work. Part of the rationale for this honor is the use of innovative methodologies for examining theoretical and policy issues. From regression analysis to path models to multiple figures and tables, the authors display adeptness in utilizing contemporary tools of social science research. Though 2010 is the latest date for data used in the study, it nonetheless contains information through the first term of New Jersey Governor Chris Christie.

However, the research does have both structural and substantive shortcomings. First, while a quote from an ELH resident was an effective technique for ending Chapter 8, that approach is unfortunately not used elsewhere in the text. Second, the authors could have improved coverage of the challenges facing the ELH project and how they are presented. For instance, material in [*148] Chapter 5 notes that the while the developer’s design for ELH avoided stigmatizing the project, street names caused a controversy over stereotyping. Further, information in Chapter 5 and 7 illustrate ELH residents’ views about the lack of activities and poor public transportation, respectively. Finally, findings reported in Chapter 8 portray the physical health of minority residents inside and outside of ELH as much worse than whites in the general population. A third general criticism pertains to repetition of results from one chapter to another. Fourth, the authors’ clear statements on behalf of the project may seem inconsistent with the effort to objectively uncover trends emanating from it.

The two most important lessons from the Mount Laurel experience with ELH pertain to the planning of the development and to the level of opposition it encountered. Given the meticulous preparation, it is understandable that the ELH project avoided many of the pitfalls of similar communities. Whether other locales have people with the expertise, patience, and commitment to create another ELH success story is not the question, but differential resources is. Even though community opposition to ELH dissipated after its construction, the three-decade odyssey to complete the project should not be minimized. After all, as UC-Berkeley Professor David Kirp observed in an October 2013 NEW YORK TIMES column highlighting the Mount Laurel achievement, it “is a truism that fear and prejudice are not readily ousted by the facts.” Perhaps the ultimate solution to affordable housing in the suburban milieu is – as Massey et al. allude to the in penultimate page of the text – a “complex intervention” to counter the root causes and damaging ramifications of poverty in America.

REFERENCES:

Gallagher, Leigh. 2013. THE END OF THE SUBURBS: WHERE THE AMERICAN DREAM IS MOVING. New York: Portfolio/Penguin Group USA.

Kirp, David. 2013. “Here Comes the Neighborhood,” NEW YORK TIMES, October 19.

Kneebone, Elizabeth, and Alan Berube. 2013. CONFRONTING SUBURBAN POVERTY IN AMERICA. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Sharkey, Patrick. 2013. STUCK IN PLACE: URBAN NEIGHBORHOODS AND THE END OF PROGRESS TOWARD RACIAL EQUALITY. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Copyright 2014 by the author, Samuel B. Hoff.