by Alexander Wohl. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2013. 486pp. Cloth $39.95. ISBN: 978-0-7006-1916-0.

by Alexander Wohl. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2013. 486pp. Cloth $39.95. ISBN: 978-0-7006-1916-0.Reviewed by Aaron J. Ley, Department of Political Science and Public Administration, University of North Dakota, aaronley [at] gmail [dot] com.

pp.58-62

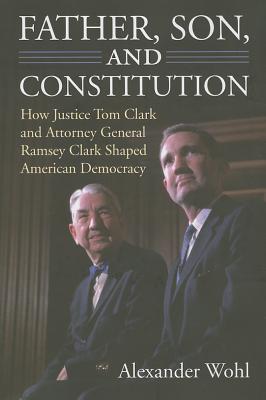

Very rarely in American history do a father and son duo exercise the power that Tom and Ramsey Clark wielded as Attorneys General, respectively for Harry S. Truman and Lyndon B. Johnson. It is made even more remarkable by the fact that this father-son duo exercised power in divergent ways and that Tom Clark was a sitting US Supreme Court Justice at the same time that Ramsey Clark was rising through the ranks of the Justice Department (Justice Clark would step down in order to pave the way for Ramsey’s nomination to Attorney General). Alexander Wohl, a former United States Supreme Court Fellow and Adjunct Professor at American University’s Washington College of Law, describes the evolution of the policy positions taken by the Clarks in his dual biography of the pair. His purpose is to “examin[e] a number of key periods, policies, and legal conflicts in which these two important legal figures were involved, [so that] we may better understand how and why our nation reaches the decisions it does today, how we strike the difficult balance between our individual liberties and our government’s power over us, and perhaps even how to apply the lessons learned to contemporary issues” (p.6).

If you are an academic that is interested in a methodologically sophisticated analysis that examines a number of different theoretical propositions, then FATHER, SON, AND CONSTITUTION may not be for you. But that does not mean that this comprehensive study lacks merit. Wohl successfully describes in detail two important historical figures who are under-studied despite their critical role in the development of American legal policy. It is for this reason that I think this book is an important contribution to the literature, especially for those who teach courses in constitutional law. If you are anything like me, you are interested in painting a vivid picture for students about the historical and political context in which the US Supreme Court is making its decisions and this book provides a number of examples of the power struggles that shaped politics from the Roosevelt Administration to the Johnson Administration and even to this day. What follows are some of the strengths of Wohl’s examination of the Clark family saga, followed with a small dose of critical commentary.

In his well-researched analysis, Wohl relies on primary and secondary sources to describe how the Clarks were raised, how they came to power, how they exercised power, and how they continue to influence American legal policy after stepping down from their positions of power. From personal interviews with [*59] Ramsey Clark to the examination of Justice Clark’s papers at the Harry S. Truman Library, Wohl sketches a portrait of the Clarks that “span[s] the ideological spectrum and reflect[s] the exigencies of their times” (p.2). We learn from this analysis that the Clarks trace their ancestry to men who fought on the side of the Confederacy during the Civil War. Ironically, both Tom and Ramsey Clark played a critical role in securing victories on behalf of the Civil Rights movement, victories that included Justice Clark’s vote in BROWN V. BOARD OF EDUCATION (1954) and Ramsey Clark’s involvement in the passage and enforcement of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

While the Clarks were significant contributors to the recognition of important civil rights, such was not always the case for the politically pragmatic Tom Clark. We learn that before Tom Clark was elevated to the Supreme Court, he held important positions in the Roosevelt Administration that required him to oversee the internment of Japanese Americans, upheld in KOREMATSU V. UNITED STATES (1944), a role that Clark would later come to regret and describe as a mistake in his professional life. Due to his loyalty to the administration, and his successful investigation and prosecution of fraud in connection with the war effort, the elder Clark was eventually promoted to Assistant Attorney General where he was head of the Antitrust Division and later the Criminal Division. When Truman became president, he elevated Clark to Attorney General where he began executing a groundbreaking legal strategy by filing amicus curiae briefs with the Supreme Court and the lower federal courts in important civil rights cases. This was made all the more remarkable by the fact that both Truman and Clark were raised in the segregated states of Missouri and Texas, respectively. Their efforts culminated in the production of the famous presidential report, “To Secure These Rights,” and Clark was responsible for “work on both legal and political aspects of the president’s civil rights agenda [that] played a significant role in helping educate the nation and setting the stage for the civil rights revolution of the 1960s” (p.93).

While Attorney General Tom Clark was on the leading edge in supporting civil rights, the Justice Department policies he formulated in the 1940s in response to the Cold War political environment were ones that Attorney General Ramsey Clark would seek to dismantle as a deputy in the Kennedy Administration and under his leadership of the Justice Department during the Johnson Administration. Tom Clark “came to be identified with the authoritarian policies he helped develop in response to both real and perceived threats of communism” (p.99). This included his political responsiveness to members of Congress on the House Un-American Activities Committee, his support for expanded warrantless wiretapping, and the creation of government employee loyalty programs. It was not until Tom Clark was a sitting US Supreme Court Justice that he began challenging executive power. Wohl goes into great detail about how Justice Clark continued interacting with executive branch officials even while disposing of cases involving the executive branch, which to the modern reader is quite remarkable given the backlash that ensued after it [*60] was reported that Justice Scalia and Vice President Cheney were hunting partners.

Wohl describes Justice Clark as a moderate jurist on the US Supreme Court, but his overall judicial philosophy evolved over the years and under the leadership of different Chief Justices. While serving on the Vinson Court, Justice Clark tended to side with the government over individual rights. In YOUNGSTOWN SHEET AND TUBE CO. V. SAWYER (1952), Justice Clark demonstrated judicial independence by voting contrary to the wishes of the president who appointed him to the bench. But when leadership of the Court changed from Vinson to Warren, Justice Clark would play a critical role in the decisions involving the desegregation of schools. Due to his upbringing and insight as a southerner, Justice Clark was particularly concerned with the implementation of judicial policies relating to desegregation of southern schools. Wohl goes into detail about the important strategic role played by Justice Clark on the Court in the area of equal protection and desegregation of schools. For instance, in COOPER V. AARON (1958) Justice Clark prepared a dissenting opinion and used the threat of publishing it as leverage to get Justice Brennan to make changes to the majority opinion. Justice Brennan, desiring a unanimous decision, incorporated all of Justice Clark’s changes.

But while Justice Clark was adjudicating cases in the marble temple, his son was quickly ascending through the ranks of the Justice Department, and Wohl describes the different constellation of forces that were confronting Ramsey while he was the country’s top law enforcement officer. The younger Clark was responsible for a number of different civil rights contributions, including the integration of Ole Miss, shepherding the Voting Rights Act of 1965 through Congress, enhancing the professionalism of local police forces, and developing crime policies that sought to attack the socioeconomic conditions producing crime. But Ramsey Clark’s worldview increasingly came into conflict with a conservative movement that was staking out a position that was tough on crime. While the elder Clark was pragmatic with respect to Justice Department policy, Ramsey was more rigid in his policy views, which led to high profile conflicts with members of Congress from both parties, and with FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. According to Wohl, “In part this was the result of his commitment to the rule of law and his unwillingness to disregard that for political gain” (p.321). Those favorable to Clark offer that commitment to the rule of law as to why he was in the unpopular position of representing such notorious international figures as Saddam Hussein, Slobedon Milosevic, and Liberian President Charles Taylor after he moved on from his position of leadership in the Justice Department.

Alexander Wohl should be commended for producing such a voluminous, detailed, and well-written examination of two under-investigated historical figures. It is replete with fascinating historical anecdotes that are certain to bring to life some of the most important political battles that shaped constitutional law and legal policy in the United States. It is an important biographical contribution that emphasizes the historical context in which Tom and Ramsey Clark were [*61] embedded, but I would hesitate to assign it to undergraduate or graduate students. The first reason is that, through no fault of his own, Wohl’s FATHER, SON, AND CONSTITUTION is largely descriptive in nature and does not make a substantial theoretical contribution to the scholarly political science or legal studies literature. In fact, Wohl is very clear about this in the beginning of the book by warning, “The goal of this inquiry is not to identify one correct answer, ideology, or legal interpretation,” but rather to understand how we reach the decisions we do, how the critical balance is struck between individual liberties and our need for order, and then finally how these understandings may be applied to contemporary conflicts (p. ). How well does he fulfll this goal? Throughout the book Wohl implicitly achieves these goals, but may have missed an opportunity to succinctly summarize these findings in the last chapter entitled, “The Clarks as a Reflection of America’s Conflicting Views on Law and Justice.”

In this final part of the book, Wohl concludes by describing Tom Clark as a pragmatist and Ramsey Clark as a rigid idealist. Here there is little discussion about how we, as a society, reach the decisions that we do or under what conditions the critical balance is struck between individual rights and societal order. Instead, we are left with a descriptive analysis of Tom and Ramsey Clark’s ideological views and how the debates during their time are still raging to this day. Furthermore, I am somewhat skeptical after reading this book that the Clarks were so instrumental in shaping American democracy as the subtitle of the book claims. First, it is not clear whether or not the Clarks were effective in reforming the bureaucracies or institutions over which they exercised leadership in a way that advanced democracy. If Tom Clark was politically pragmatic and responsive to forces that actually stunted the development of American democracy during a critical part of Cold War history, then are not other forces at work in shaping legal policy during this time? Furthermore, what really explains the different approaches of the Clarks in the area of Civil Rights policy? Was it really their early experiences with Civil Rights that influenced their policy positions? I am inclined to agree with Charles Epp (1998), who contends that a lot of this change occurs from well-organized advocacy groups pressing for policy change; perhaps this explains why Ramsey Clark, unlike his father, was so strongly in support of individual rights as US Attorney General.

Overall, FATHER, SON, AND CONSTITUTION serves its intended audience well by illustrating in detail the Clarks’ role in the development of US legal policy. It is a book that is very well-written and organized, and Wohl does a nice job of weaving together the narratives of the Clarks by using appropriate primary and secondary sources. I will certainly be using examples and anecdotes from FATHER, SON, AND CONSTITUTION to bring to life the high-profile conflicts that shaped legal policy and the Constitution in the courses I teach.

REFERENCES

Epp, Charles. 1998. THE RIGHTS REVOLUTION: LAWYERS, ACTIVISTS, AND SUPREME COURTS IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE. Chicago: University of [*62] Chicago Press.

CASE REFERENCES

BROWN V. BOARD OF EDUCATION, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

COOPER V. AARON, 358 U.S. 1 (1958).

KOREMATSU V. UNITED STATES, 323 U.S. 214 (1944).

YOUNGSTOWN SHEET & TUBE CO. V. SAWYER, 343 U.S. 579 (1952).

Copyright 2014 by the Author, Aaron J. Ley.