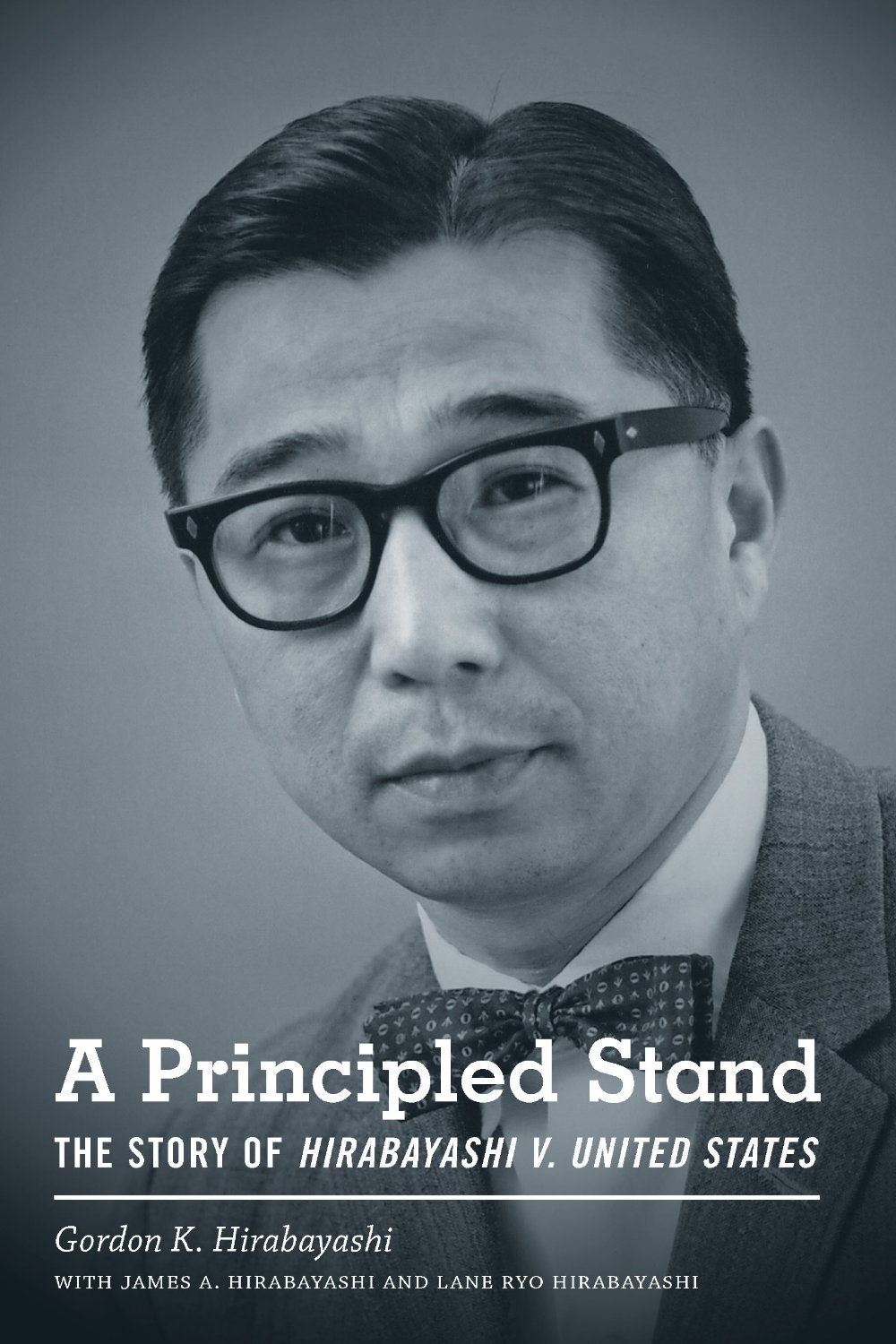

by Gordon K. Hirabayashi with James A. Hirabayashi and Lane Rio Hirabayashi. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2013. 217pp. Cloth, $29.95. ISBN: 978-0295992709.

by Gordon K. Hirabayashi with James A. Hirabayashi and Lane Rio Hirabayashi. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2013. 217pp. Cloth, $29.95. ISBN: 978-0295992709.Reviewed by James C. Foster, Political Science, Oregon State University-Cascades. Email: james.foster [at] osucascades.edu.

pp.77-82

In 1955, Pete Seeger, the recently deceased folk singer and activist, famously sang “Oh, when will they ever learn?” Twelve years earlier, in the Summer of 1943, Gordon K. Hirabayashi journaled: “In a position and circumstance like [mine], a fellow has a chance to do a lot of meditating and reflecting. . . . [T]he stars that I have seen for years had a fresh appearance. . . . They seemed to be viewing the feverish ways of man, saying, “When will he ever learn?” (p.146). Hirabayashi had cause to reflect. His “position and circumstance” in that mid-World War II Summer found Hirabayashi temporarily stranded on a deserted roadside near Umatilla, Oregon, awaiting a lift in the wee hours of the morning, while “thumbing” his way from Spokane to Tucson to serve a nine-month sentence, following a conviction that had been upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in HIRABAYASHI V. UNITED STATES (1943). Hirabayashi had been convicted of violating – he would say resisting – the federal curfew and exclusion orders mandated by a series of post-Pearl Harbor presidential, legislative, and military edicts targeting persons “of Japanese descent.” In a deeply ironic episode, because as the U.S. Attorney in Spokane told Gordon “I don’t have travel funds” (p.145), Hirabayashi had to devise his own way to travel 1,600 miles to the Catalina Federal Honor Camp in order to serve his time. His trek took two weeks.

Both Pete Seeger and Gordon Hirabayashi took principled stands throughout their lives. Each, in his own honorable way, touched untold people’s lives while furthering social justice. Both suffered consequent slings and arrows. Seeger’s tool was his banjo, emblazoned with the Guthrie-like slogan: “THIS MACHINE SURROUNDS HATE AND FORCES IT TO SURRENDER.” Hirabayashi’s unwaveringly resolute approach, while less dramatic, was no less effective. Equally, Seeger and Hirabayashi employed the power of words. Each lived exemplary lives.

However inspiring and pertinent a comparison of Seeger’s and Hirabayashi’s principled stands may be, Review readers rightly expect work product assessments, not testimonials. Alright then: A PRINCIPLED STAND is an essential supplement. It adds previously missing biographical and sociological aspects to the literature parsing a telling episode in the “Politics of Prejudice” (Daniels, 1962), culminating when the United States government, after the Pearl Harbor attack, initially regulated the free movement of, then rounded up, excluded, and confined in concentration camps, nearly 120,000 persons of [*78] Japanese descent from February 1942 until January 1945 (Kashima, 2003). Two thirds of these people were American citizens, including Gordon Hirabayashi.

A brief sidebar: the book’s subtitle is misleading. A PRINCIPLED STAND is so much more than strictly the story of HIRABAYASHI V. UNITED STATES, the 1943 U.S. Supreme Court decision. The subtitle would more accurately read “The Story BEHIND HIRABAYASHI V. UNITED STATES,” or “The Story UNDERNEATH HIRABAYASHI V. UNITED STATES.” What’s in a preposition? Better still: “HIRABAYASHI V. UNITED STATES: THE BACKSTORY.” Then again, it would be hard to improve on the title of Theodore Dreiser’s magnum opus: AN AMERICAN TRAGEDY. Regardless, Gordon Hirabayashi tells HIS story. He also shares stories about his family, his friends, and his associates. Additionally, he relates engaging and revealing encounters with a variety of bit players in this very American chronicle. His narrative is historically mortifying. It also is heart-warming and personally triumphant.

Hirabayashi tells his story with the necessary assistance of his brother James, and his nephew Lane. Hirabayashi died on January 2, 2012. A PRINCIPLED STAND was published in 2013. James and Lane Hirabayashi together gave their esteemed relative his voice back. They did so by “rearranging and lightly (and silently) editing Gordon’s words” (pp.xv-xvi). The result is a seamless chronicle.

In order to appreciate fully the political significance of Hirabayashi’s story, one must contextualize it by situating A PRINCIPLED STAND within the recent flowering of scholarship that scrutinizes A TRAGEDY OF DEMOCRACY: JAPANESE CONFINEMENT IN NORTH AMERICA (Robinson 2009), as well as the lineage of this scholarship.

Hirabayashi continues the process of deconstructing – thereby delegitimizing – the official post-December 7, 1941 construction of Japanese citizens as members of an inscrutable, unassimilable race who could be incarcerated indefinitely without constitutional scruple. This process of analyzing, criticizing, and disarming the dominant “internment” narrative has been going on since December 18, 1944. The three dissents in KOREMATSU V. UNITED STATES, (1944), the most well-known of the four Japanese removal cases (HIRABAYASHI, YASUI V. UNITED STATES(1943), KOREMATSU, EX PARTE ENDO (1944) ), belated though they were, are prominent instances of incipient, and flawed, rejections of the prevailing narrative. That chronicle is driven by a “racial schema” (see Kang 2002; Kang 2004; Kang March 2005a; Kang 2005b). “[I]n any interaction, we apply rules of racial mapping to place a human being or a group of human beings into a racial category...If we apply this model to the internment, we see that the rules of racial mapping forced the Japanese in America into a racial category: Oriental” (Kang 2004, p.956; compare Muller 2002; Muller 2003).

Hirabayashi’s violation of the curfew order was upheld unanimously, but Justices Robert Jackson’s, Frank Murphy’s, and Owen Roberts’ KOREMATSU dissents are early departures from the “treacherous Yellowface” narrative (see Thompson 1978; Aoki [*79] 1996; Lyman 2000; Yamamoto et. al. 2013). The next, more profound yet still not fundamental, departure involved fortuitous discoveries and heroic lawyering. Auspiciously uncovered key documents, unearthed by researcher Aiko Yoshinaga-Herzig and historian Peter Irons, documented government racist perfidy (see Irons 1989; Maki 1999; Grodzins 1949). For example, in 1942 John L. DeWitt, Commanding General of the Western Defense Command, said before the U.S. House of Representatives, “It makes no difference whether the Japanese is theoretically a citizen – he is still a Japanese... A Jap is a Jap” (Kang 2004, p.987). The damning documents enabled Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu, Minoru Yasui, and Gordon Kiyoshi Hirabayashi to successfully file petitions in federal courts to have their respective convictions vacated under writs of error coram nobis. “If the story of the 1940s is tragic, the story of the 1980s is euphoric”(Kang 2004, p.975). It is euphoric because of the fact that, “all three branches of government [took] responsibility for the internment and also . . . [apologized;] a remarkable victory”(Kang 2004, p.976). Here are Hirabayashi’s meditations on his tardily vindicated decision to resist the Curfew and Exclusion orders:

“In times of crises, when the usual sources of direction and “landmarks” for decision making aren’t available, what constitutes realistic, practical behavior? What role does idealism play in such circumstances? Sailing through uncharted waters, what becomes realism? The answers to these questions are not easy. But one needs something more than the truism that “idealism” is all right, but in a crisis one must be “realistic.” In fact, my story illustrates that in a crisis, the opposite formula may be just as true” (pp.189-190).

These reflections remind me of Antonio Gramsci’s aphorism: “I’m a pessimist because of intelligence, but an optimist because of will.” Hirabayashi’s willful resistance was grounded in his Quaker faith and his resolute commitment “to take first-class citizenship seriously in spite of the knowledge of second-class status of Japanese”(p.28). Both foundations are apparent in this powerful “Prison Meditation”(p.103) that Hirabayashi wrote while serving time for the curfew violation in the King County, Washington jail. His statement is reminiscent of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s 1963 Letter From Birmingham Jail:

“The only way to pierce the darkness, to overcome it, is not by a darker darkness or more of it. There must be light. In the same way, we cannot build within ourselves forces for a just and durable peace by cooperating and participating in the very forces that instigate hate, distrust, suspicion, prejudice, totalitarian attitudes. Love is the only thing powerful enough to overcome hate, suspicion, and so forth. Love is the only thing that nurtures and develops personalities” (p.110).

In a striking passage, Gordon Hirabayashi observed, “I do not know why, but Jesus seemed to teach through personal example, and he always worked from the personal angle” (p.112). There is not a shred of pretense in his statement. On the contrary, these words capture Hirabayashi’s modest and fierce belief that “I can’t [obey the Curfew [*80] Order], or I’m not true to myself, and if I’m not, I’m not a very good citizen to anybody” (p.57).

The third phase in the unfolding efforts to repudiate completely the four Japanese removal cases, together with the legal doctrines and historical precedents for which they stand, has taken the form of a withering intellectual assault on what law professor Jerry Kang has characterized as “the circle of absolution” (Kang 2004:, p.986; Kang 2005, p.263). Kang writes:

“In the end, according to the official line, was anyone responsible for this grotesque, racist violation of civil rights? To be sure, both the President and Congress have apologized. But according to the official legal story it was not their fault. Remember Endo [Gudridge]. The [War Relocation Authority] and a handful of government officials in the Army, the Department of War, and the Department of Justice are the only ones to blame. No institutional responsibility has been taken, especially on the part of the Judiciary

But the official line is not the truth. The suppressed smoking gun evidence, as damning as it is, would not have altered the 1940 results. This is not because the suppression was in any way trivial or excusable. This is so because the Court, thinking through its racial schemas, had no intention of interfering with the internment, whatever the evidence” (Kang 2004, p.986).

A PRINCIPLED STAND incorporates Gordon Hirabayashi’s commendable life into this emerging revisionist history. After the war he earned a doctorate in sociology, and taught college in the Middle East and Canada. He never stopped challenging the wrong he and others suffered. Gordon’s example is particularly timely in our post-9/11 world, a milieu in which the perils of “Walking while Muslim” (Chon and Artz 2005; also see Saito 2001) are compounded by the circumstance that “the HIRABAYASHI case arguably still ‘lies about like a loaded weapon’” (Muller May 2010, p.1335 (quoting KOREMATSU V. UNITED STATES, at 246 (1944) (Jackson, J., dissenting)); also see Kang 2005b; Kang 2008). The U.S. Supreme Court decision upholding Gordon’s convictions for acts of conscience – resisting the curfew and exclusion orders – remains a potential cudgel because the underlying racial schema animating that ruling remains. “Hiding in the shadow of KOREMATSU,” HIRABAYASHI can fuel fears of “the radical Islamist” (Muller 2010, pp.1334; 1386). Its racist rationale remains available to blur and to undercut life-and-death distinctions between “the real harm that some violent organizations and individuals intend for the United States [and] the cataclysmic designs we project onto the caricature of the ‘jihadi’ and the ‘Islamofascist’ that has haunted the national consciousness since September 11” (Muller 2010, p.1386).

During the 1987 Constitution Bicentennial, I received a grant from the Oregon Council for the Humanities to travel around the state, Chautauqua-style, lecturing and showing an accompanying slide show about “Due Process in America.” Part of my presentation addressed the imprisonment of Japanese Americans and the consequent Japanese American removal [*81] cases. Throughout my talk one evening in the coastal town of Florence, Oregon, a man sat in the back of the room, scowling deeply. Following the Q&A, during which he said nothing, he approached. Shaking my hand, the sexagenarian began: “I liked your talk young fellow.” He continued, echoing General DeWitt: “I liked your talk, but I was a sailor in The War and, as far as I’m concerned, a Jap is always a Jap.” If only this old salt could have made the acquaintance of Gordon K. Hirabayashi.

REFERENCES:

Aoki, Keith. 1996. “‘Foreign-ness’ & Asian-American Identities: Yellowface, World War II Propaganda, and Bifurcated Racial Stereotypes.” UCLA PACIFIC AMERICAN LAW JOURNAL 4:1.

Chon, Margaret and Donna E. Artz. 2005. “Judgments Judged and Wrongs Remembered: Examining The Japanese American Civil Liberties Cases on Their Sixtieth Anniversary: Walking While Muslim.” LAW AND CONTEMPORARY PROBLEMS 68:215.

Daniels, Roger. 1962. THE POLITICS OF PREJUDICE: THE ANIT-JAPANESE MOVEMENT IN CALIFORNIA AND THE STRUGGLE FOR JAPANESE EXCLUSION. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Dreiser, Theodore. 1925. AN AMERICAN TRAGEDY. New York, NY: The Sun Dial Press.

Grodzins, Morton. 1949. AMERICANS BETRAYED: POLITICS AND THE JAPANESE EVACUATION. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Gudridge, Patrick O. 2003. “Remember ENDO?” HARVARD LAW REVIEW 116:133.

Irons, Peter. 1989. JUSTICE DELAYED: THE RECORD OF THE JAPANESSS AMERICAN INTERNMENT CASES. Wesleyan.

Kang, Jerry. 2002. “Thinking Through Internment: 12/7 and 9/11.” ASIAN LAW JOURNAL 9:195.

Kang, Jerry. 2004. “Denying Prejudice: Internment, Redress, and Denial.” UCLA LAW REVIEW 51:933.

Kang, Jerry. 2005a. “Trojan Horses of Race.” HARVARD LAW REVIEW 118:1489.

Kang, Jerry. 2005b. “Judgments Judged and Wrongs Remembered: Examining The Japanese American Civil Liberties Cases on Their Sixtieth Anniversary: Watching The Watchers: Enemy Combatants in The Internment’s Shadow.” LAW & CONTEMPORARY PROBLEMS 68:255.

Kang, Jerry. 2008. “Dodging Responsibility: The Story of Hirabayashi v. United States.” In Rachel F. Moran and Devon Wayne Carbado, RACE LAW STORIES. New York, NY: Foundation Press.

Kashima, Tetsuden. 2003. JUDGMENT WITHOUT TRIAL: JAPANESE AMERICAN IMPRISONMENT DURING WORLD WAR II. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

Lyman, Stanford M. 2000. “The ‘Yellow Peril’ Mystique: Origins and Vicissitudes of a Racist Discourse.” INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF POLITICS, [*82] CULTURE, AND SOCIETY 13:683.

Maki, Mitchell T., Harry H. Kitano, and S. Megan Berthold. 1999. ACHIEVING THE IMPOSSIBLE DREAM: HOW JAPANESE AMERICANS ACHIEVED REDRESS. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Muller, Eric L. Spring 2002. “12/7 and 9/11: War, Liberties, and The Lessons of History.” WEST VIRGINIA LAW REVIEW 104: 571.

Muller, Eric L. Fall 2003. “Reflections on The Criminal Justice System after September 11, 2001: Inference or Impact? Racial Profiling And The Internment’s True Legacy. OHIO STATE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW 1:103.

Muller, Eric L. May 2010. “Hirabayashi and The Invasion Evasion.” NORTH CAROLINA LAW REVIEW 88:1333.

Robinson, Greg. 2009. A TRAGEDY OF DEMOCRACY: JAPANESE CONFINEMENT IN NORTH AMERICA. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Saito, Natsu Taylor. May 2001. “Symbolism under Siege: Japanese American Redress and the 'Racing’ of Arab-Americans as ‘Terrorists.’” ASIAN LAW JOURNAL 8:1.

Seeger, Pete. 1955. "Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” Lyrics © The Bicycle Music Company.

Thompson, Richard Austin. 1978. THE YELLOW PERIL, 1890-1924. New York, NY: Arno.

Yamamoto, Eric K., Margaret Chon, Carol L. Izumi, Frank H. Wu, and Jerry Kang. 2013. 2nd ed. RACE, RIGHTS, AND REPARATION: LAW AND THE JAPANESE AMERICAN INTERNMENT. Aspen.

CASE REFERENCES:

EX PARTE ENDO, 323 U.S. 282 (1944).

HIRABAYASHI V. UNITED STATES, 320 U.S. 81 (1943).

KOREMATSU V. UNITED STATES, 320 U.S. 314 (1944).

YASUI V. UNITED STATES, 320 U.S. 115 (1943).

Copyright 2014 by the Author, James C. Foster.