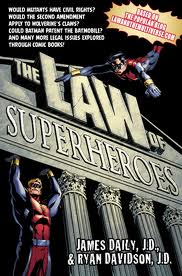

by James Daily and Ryan Davidson. New York: Penguin Books, 2012. 304pp. Cloth $26.00. ISBN: 978-1-592-40726-2.

by James Daily and Ryan Davidson. New York: Penguin Books, 2012. 304pp. Cloth $26.00. ISBN: 978-1-592-40726-2. Reviewed by Susan Burgess, Department of Political Science, Ohio University. burgess [at] ohio.edu

pp.129-131

Nerds are popular these days, judging from the success of television shows such as The Big Bang Theory, which features a group of four socially awkward male physicists negotiating a world outside the lab that is decidedly not nerdy. The Big Bang nerds are obsessed with superheroes, who also happen to be quite popular right now. The Avengers was the top grossing movie of 2012, bringing in nearly $900 million worldwide, followed by The Dark Knight Rises at $640 million. While many academics may not follow popular culture very closely, perhaps we should, as such matters may well influence the way that the vast majority of people understand topics that academics do care deeply about, such as law and politics. The Law Of Superheroes offers an accessible entrée into this world, providing an interesting mash-up of law and pop culture that draws hypotheticals from the world of superheroes to the end of better explaining complex legal doctrine.

This book grew out of the blog Law and the Multiverse, which the authors co-founded. The blog includes regular commentary on law as it emerges in the context of various forms of pop culture including contemporary films (such as The Hobbit), comics (such as The Green Lantern), and young adult novels (such as Little Brother). It also offers interviews with artists such as Mark Waid and Daniel Reeve of Daredevil and Lord of the Rings fame.

The book that resulted from the blog is much more focused, using superheroes to explain a variety of doctrinal areas including constitutional law, criminal law, evidence, criminal procedure, tort law and insurance, contracts, business law, administrative law, intellectual property, and international law. Nerds familiar with Superman, Batman, Hawkman, The Flash, Green Lantern, The Avengers, Captain America, Iron Man, and a host of other popular characters will enjoy seeing the stories of their heroes used to illustrate basic points in each of these areas as the universes of fictional comic books are applied to various terrains of U.S. law. Questions explored include whether Superman violates privacy laws when he uses his X-ray vision, whether the Second Amendment protects Iron Man’s suit, whether the Joker is legally insane, whether Nitro is guilty of attempted murder if he burns Wolverine (knowing full well that Wolverine will survive), whether Clark Kent is responsible for Superman’s tax bill, whether an immortal can collect Social Security benefits forever, whether Batman could patent the Batmobile, whether mutants (who are frequently discriminated against in the Marvel Universe) are due civil rights protections, and whether heirs of superheroes who come back from the dead are able to keep inherited property post-resurrection. [*130]

Just reading this partial list of topics made me smile. Who wouldn’t be entertained by such a refreshingly original approach to often dry doctrinal questions? In addition, Superheroes increased my understanding of doctrinal issues in several areas with which I was less familiar, providing several clarifying examples that will likely be quite useful in the classroom. And this is exactly the response that Daily and Davidson authors seek: drawing people further into the study of law on the basis of interesting, accessible, and popular comics, they hope to expand popular knowledge of basic legal doctrine. There is no question that this book offers a clear and creative description of basic legal concepts, disrupting the often much too self-serious tone of academic legal discourse while demystifying complex ideas that are often thought to be better left to legal experts. As such the book has a distinctly populist feel, as it nicely performs the democratic potential of popular culture.

That said, this book is definitely aimed at comic enthusiasts, experts in their own right, who will be delighted by the detailed textual renderings of various superhero universes, as well as the many graphic illustrations that are reproduced directly from actual comic book panels. Despite the authors’ clear desire to appeal to a broad audience, some of the details of these universes will likely be unfamiliar and inaccessible to the uninitiated (performing an interesting reversal perhaps without meaning to). Given the aims of the book, I cannot fault it for lacking an introduction and / or a conclusion that analyzes the value of the approach taken here, perhaps by relating it other similar mash-ups or to other work in the field of cultural studies more generally. Nonetheless, the book did lead me to long for exactly that.

Readers who experience a similar longing might consult Dana Nelson’s Bad for Democracy: How the Presidency Undermines the Power of the People, which includes a very interesting American Studies treatment of how the president came to be seen as a superhero whom the people have come to rely on to save them from various foreign and domestic perils, allowing him to exercise ever greater and perhaps even unlimited superpowers, all the while diminishing the role of popular participation in the public sphere. Geographer Jason Dittmer’s recently released book Captain America and the Nationalist Superhero: Metaphors, Narratives, and Geopolitics explores the understandings of national identity that often underlie superhero comics, critically examining American exceptionalism and the use of moralistic power in the United States, Canada, and Britain. While these books have critical aims and areas of focus that are somewhat distinct from The Law of Superheroes, they nicely display the ways that superhero pop culture can be used in a populist as well as a critical manner, an endeavor that seems increasingly important for understanding contemporary U.S. law and politics. It behooves all of us, academics included, to pay careful attention to these trends and the scholarship that helps us to understand their import. If, as New York Times film critics A.O. Scott and Manohla Dargis have recently argued, understanding the representations of superheroes is central to understanding the patterns of acceptance and challenge [*131] to wartime presidents such as Barack Obama, pop culture is likely to continue to be a significant aspect of the field for some time to come.

REFERENCES:

Dittmer, Jason. 2013. Captain America and the Nationalist Superhero: Metaphors, Narratives, and Geopolitics. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Nelson, Dana. 2010. Bad for Democracy: How the Presidency Undermines the Power of the People. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Scott, A.O. and Manohla Dargis. 2013. “Movies in the Age of Obama.” New York Times. January 16.

Copyright 2013 by the Author, Susan Burgess